;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

“He who controls the spice, controls the universe.” Such were the words uttered by the main character of the movie Dune based on the Frank Herbert science fiction epic of the same name. In the story, the spice was the lifeblood of a vast empire. For the leaders of this empire, it was essential that at all times ‘the spice must flow.’

The spice trade of the Dune movie was no doubt inspired by the historical trade in aromatics from ancient times to the present. At various periods in history,spices have been as valuable as gold and silver. According to a 15th century saying: “No man should die who can afford cinnamon.”

The aromatic substances were even more mysterious as they were connected in many cultures with the idea of a faraway paradise -- Eden. The Muslim writer al-Bukhari wrote that Sumatran aloeswood known as `Ud in Arabic filled the censers of Paradise. Ginger was the other major aromatic of Paradise in Muslim tradition. In the Travels of Sir John Mandeville it is said that the aloeswood of the Great Khan came from Paradise.

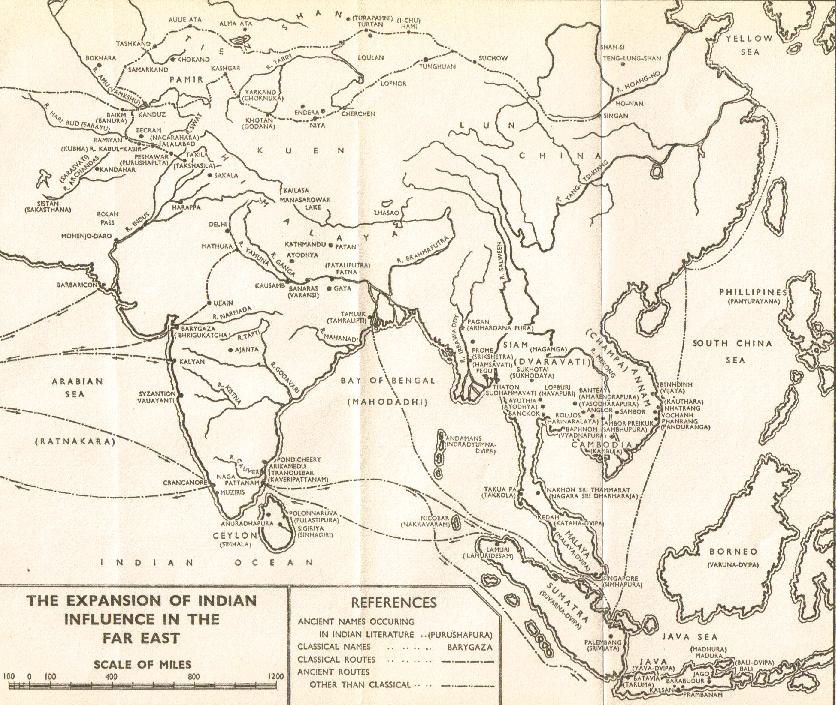

We will show that the famed spices which traveled from Africa to the Arabian traders and from thence to the markets of the classical Mediterranean world had their ultimate origin in Southeast Asia. The aromatic trail known as the “Cinnamon Route” began somewhere in the Malay Archipelago, romantically known as the “East Indies,” and crossed the Indian Ocean to the southeastern coast of Africa.

The spices may have landed initially at Madagascar and they eventually were transported to the East African trading ports in and around the city known in Greco-Roman literature as Rhapta. Merchants then moved the commodities northward along the coast. In Roman times, they traveled to Adulis in Ethiopia and then to Muza in Yemen and finally to Berenike in Egypt. From Egypt they made their way to all the markets of Europe and West Asia.1

The beginning of the trade is hinted at in Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions during the New Kingdom period about 3,600 years ago. The Pharoahs of Egypt opened up special relationships with the kingdom of Punt to the south. Although the Egyptians knew of Punt long before this period, it was during the New Kingdom that we really start hearing of important trade missions to that country that included large cargoes of spices. Particularly noteworthy are the marvelous reliefs depicting the trade mission of Queen Hatshepsut of the 18th Dynasty

The idea of an ancient trade route to the east for spices and also precious metals like gold and silver is not new. The Jewish historian Josephus, writing in the first century AD, offered his explanation of the Biblical story of Solomon and Hiram’s joint trade mission to the distant land of Ophir. In his Antiquities of the Jews, he said the voyages which began from the Red Sea port of Ezion-geber were destined for the island of Chryse far to the east in the Indian Ocean. Ezion-geber was near the modern city of Eilat in Israel and the trade voyages took three years to complete according to the Old Testament account2. Where then was the island of Chryse mentioned by Josephus? Greek geographers usually placed it east of the Ganges river mouth. Medieval writings placed it near where the Indian Ocean met the Pacific Ocean. In modern times, Chryse has been equated by scholars with the land known in Indian literature as Suvarnadvipa. Both Chryse and Suvarnadvipa mean “Gold Island.” The latter was also located in Indian writings well to the east of India in the “Southern Ocean” and is identified by most scholars with the Malay Archipelago (“the East Indies”).

Josephus’ theory of voyages to Southeast Asia was supported indirectly about a half-century later by Philo of Byblos who translated the History of Phoenicia by Sanchuniathon. This translation was originally considered a fraud by modern scholars, but discoveries from Ras Shamra in the Levant indicate Philo’s work was authentic. They are important because they come from a different historical source than the Old Testament account.

Philo records the Phoenician version of Solomon and Hiram’s trade mission to Ophir. What is interesting is how Philo’s account allows us to interpret some arcane Hebrew passages. He outlines journeys into the Erythraean Sea (Indian Ocean) that took three years to complete. The items brought back from the journey were apes, peacocks and ivory all products of tropical Asia and all included along with other goods in the Biblical account.

Philo’s interpretation of Sanchuniathon’s history uses words for the products of the voyages which clearly point to tropical Asia unlike the strange terms used a thousand years earlier in Solomon’s time. The romantic idea of distant Ophir may have inspired the explorer Magellan on his circumnavigation voyage around the world in the 16th century. The explorer replaced geographical locations in his reference books with the names “Tarsis and Ofir,” the equivalent in his time of Biblical “Tarshish and Ophir.”3 He actually set a course on the latitude of one of these locations before reaching the islands of the Visayas from the East.

In the medieval and early colonial period, commentators on classical Greco-Roman literature first began hinting that the Cinnamon Route might trace eventually from Africa to the east in Asia. Many of the terms used for spices in early works are obscure and can be difficult to identify. The commentators interpreted these terms into the contemporary language at a time when the knowledge of the world had greatly increased. In most cases, we can confidently associate these latter spice names with species that we know today.

Thus, when the ancient writer Pliny mentions tarum as a product of East Africa we understand it as aloeswood because later commentators translate tarum with a word that is no longer obscure: lignum aloe “aloeswood.” By the time of the commentators, the source of the aloeswood was already well-known. Pliny mentions tarum as coming from the land that produced cinnamon and cassia in Africa. But the commentators give it an identity which clearly indicates a tropical Asian origin in their time.

So why were these Asian products turning up in African markets? Pliny is the only writer who attempts an explanation and the related passages have been the source of much scholarly controversy. The details will be discussed later in this book, but the historian James Innes Miller was possibly the first modern scholarto put on his glasses and use Pliny and other evidence to suggest that Austronesian traders had brought spices to African markets via a southern maritime route. Miller connected the spice route with the prehistoric settlement of Madagascar by Austronesian seafarers. spices from southern China and both mainland and insular Southeast Asia were brought by Austronesian merchants whom he associates with the people known to the Chinese by the names Kunlun and Po-sse.

Miller’s book was the defining work of his time and it still has a profound influence on historians of trade and seafaring. However, classical historians and philologists had mixed views on Miller’s thesis. A number of alternative theories sprung up and Miller was criticized, sometimes rightfully so, with using too many loosely-established ideas to support his argument. One of our main goals will be to use newer evidence along with some apparently missed by Miller to show that, for the most part, his idea of a southern transoceanic route was correct.

In addition to Miller’s Cinnamon Route, there also existed a “Clove Route” to China and India.

The evidence for these early spice routes comes from every available field including history, archaeology, linguistics, genetics and anthropology. For example, we can show by a process of elimination that a southern route for tropical Asian spices into Africa is historical. The exact details of this route are not known to us from history but the route itself is the only reasonable conclusion given the historical sources at our disposal. We can then bolster the testimony of history by bringing in supporting evidence from other fields.

One way we do this is to show that certain cultural items that came from Southeast Asia, or at least tropical Asia, were diffused first to the southeastern coast of Africa before moving northward at dates that are supportive of our thesis. One example is the diffusion of the domestic chicken (Galllus gallus) to Africa. The oldest archaeological remains of this species may date back to 2,800 BCE from Tanzania.4 The earliest similar evidence in Egypt is not earlier than the New Kingdom period about 1,000 years later. To support this finding, there is additional evidence provided by the presence of the double outrigger5, barkcloth, various types of musical instruments6 and other cultural items present on the southeastern African coast. Possibly also the distribution of the coconut crab7, the world’s largest land-based invertebrate also provides evidence for this early southern contact.

An important factor in ascertaining the old spice routes from Southeast Asia is the trail of cloves from Maluku and the southern Philippines north to South China and Indochina and then south again along the coast to the Strait of Malacca. From there the cloves went to India spice markets and points further west. This north-south direction of commerce through the Philippines has recently been recognized by UNESCO as part of the ancient maritime spice route. The Philippine-Maluku hub persisted into Muslim times and is chronicled in Arabic historical and geographic writings.

While the clove route started in the south, cinnamon trade began in the north. The cinnamon route started in the cinnamon and cassia-producing regions of northern Indochina and southern China and then likely proceeded from South China spice ports southward during the winter monsoon down the Philippine corridor. The route likely turned southeast at that point to Sumatra and/or Java to pick up different varieties of cinnamon and cassia along with aloeswood and benzoin. From southwestern Indonesia the voyage then took the Austronesian merchants across the great expanse of the Indian Ocean to Africa.

Linguistically the clove route is supported by the distribution of names for ginger in the Malay Archipelago. These appear to have followed the clove route from China through the Philippines to the rest of insular Southeast Asia.

In the medieval Chinese and Muslim texts we first get specific details about these routes although they probably were unchanged from the ones used centuries or thousands of years earlier. The Chinese records in particular give detailed itineraries including directions and voyage length for each stop along the way to the southern spice markets. Of particular importance are the entrepots known to the Chinese as Sanfotsi and Toupo. The same marketplaces were likely known to the Muslim geographers likely by the names of Zabag and Waqwaq respectively.

Like Chryse of the Greeks and Suvarnadvipa of the Indians, these entrepots were a source of wonder and literary romance. In the One Thousand and One Nights, Sinbad travels to Zabag on one of his voyages and the islands of Waqwaq are the setting for the adventure of Hassan of Basra. Indian literature also abounds in tales of voyages to the islands of gold by those in search of treasure, either material or spiritual.

From the Arabic literature, we start to learn of first-hand accounts of trade and other voyages by mariners from Southeast Asia to Africa. Previously, we had only the vague accounts of Solomon’s journey and Pliny’s brief descriptions of long sea voyages from or to the cinnamon country. The Muslim works tell us of ships and people from Zabag and Waqwaq coming to African ports for trade and even on occasion to conduct military raids. The records give the impression of well-established trade relationships, but just how long did these long-distance ties exist before the Muslim writings?

We believe is a strong case for this trade opening up by at least the New Kingdom period in Egypt. At that time, voyages to the divine land of Punt became more frequent with large fleets bringing back impressive hauls of tribute for the Pharaoh. While the hard evidence is still fragmentary, the quantity and quality of this evidence is still comparable to those of other established theories. We simply come to the most logical conclusions based on the historical records, and how these records should be interpreted based on the evidence.

Rome’s discovery of the monsoon trade winds did not have any significant impact as the Roman ships mainly plied the waters between the Ptolemaic port of Berenike and the ports along the coast of eastern Africa and western India. The Romans apparently did not interfere much at these ports and only established minor trading colonies if any in these areas. The wave of Islam into East Africa was probably the strongest factor in closing the southern spice route.

Muslim traders managed to convert the local populations, and in the process, must have greatly complicated preexisting trade relationships. The Muslim merchants in their dhows moving eastward would have eventually discovered the sources of cinnamon and cassia. Then it was only a matter of time before the caliphate would be able to eliminate the African ports in favor of direct import to Arab entrepots. This was not an immediate process though.

The Muslim geographers and historians still record trade activity between Africa and Southeast Asia in aloeswood, tortoise-shell, iron and other products centuries after the Arabs had established themselves on the Tanzanian coast. By the time the Portuguese reached this area though it appears this trade had disappeared. All that was left were traces of the Austronesian contact including the local boats with their outriggers and lateen sails made of coconut fiber.

With the end of the cinnamon route and the advent of the European control of the spice trade, the Austronesian component of this commerce almost completely faded away. However, some three thousand years of spice trade from the New Kingdom to the late Muslim period left a lasting legacy that reshaped the world. The vision of an El Dorado of gold and spices tempted romantics and kings alike. For centuries, the Arabs had controlled the Mediterranean part of the spice trade by keeping secret the monsoon sources of the precious commodities. Eventually the Roman empire discovered the monsoon routes as opposed to earlier costly voyages that involved closely following the shoreline. However, it took some time before they could discover the real sources of the spices they treasured so much.

When the Alexandrian merchant Cosmas Indicopleustes ventured to find these sources in the sixth century ACE, many of these secrets were just coming to light. However, it was a little too late. The meteoric rise of Islam closed off any further European exploration or exploitation of the spice routes. Conversely, a whole new world was opened up for the merchants of the Muslim world. Their newly found power allowed them to venture deep into Asia as never before. The Islamic texts give the first detailed descriptions of the emporiums of the East. By at least the ninth century, a massive trade ensued between the two regions greatly enriching the the Islamic caliphate. Magnificent cities and buildings were constructed throughout the Muslim lands at the same time that Europe sunk into the dark ages. The Arabic writers also tell of great kingdoms and empires of the East including the fabled cities of the Khmers and the island domains of the Mihraj (Maharaja) of Zabag.

Europe would get another chance centuries later when a charismatic leader arose out of a hitherto unknown nomadic tribe of the steppe. Chingiss Khan, also known as Genghis Khan, rode out of the wastelands of Central Asia with his Mongol armies on epic conquests. Among the empires destroyed in the Great Khan’s path was the Islamic Caliphate. The fall of Baghdad again opened the Silk Road and the maritime spice route to the merchants and adventurers of Europe. One of the first to take up the challenge of the East was Marco Polo. The records of his travels along with those of other Europeans who ventured east rekindled the urge to link with the long-lost spice Eden of the east. The Portuguese were the first to take up the gauntlet establishing bases at Goa in India and Malacca on the Malay Peninsula. Others followed including the powerful Dutch East Indian Company.

The quest for spices and precious metals ushered in what is known as the Age of Exploration. Magellan’s personal documents indicated his desire to find the golden islands of Tarshish and Ophir. The explorer Sebastian Cabot was appointed as commander of an expedition “to discover the Moluccas, Tarsis, Ophir, Cipango and Cathay.” The fight to control the flow of cloves, nutmeg, black pepper, gold, silver and other commodities led to the circumnavigation of Africa and the world, and the exploration of the Western hemisphere and the Pacific Ocean.

The coming of the Europeans nearly completely excluded the native Austronesian merchants from the trade. The same people who in the Muslim annals were sailing to East Africa to engage in commerce now where often prevented even from participating in merchant activity from city to city or island to island in their own region. Only after Southeast Asia freed itself from Western colonialism has this ancient wonderland of entrepots regained direct control its own trade again. Today, the nations of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) have formed a unique organization designed to enhance commerce in the region. Indeed, ASEAN is really the model for the entire Asian region. Even developed Asian nations like Japan and South Korea have looked to ASEAN as the model for regional trade cooperation.

Today, manufactured goods from sneakers to computers are more important exports that spices or precious metals, although these latter items continue to hold their own. The region has also come to be a leader in a completely different type of trade – the human trade. Southeast Asia is the world’s largest exporter of human labor. Seafarers , nurses, doctors, domestics, constructions workers, computer programmers and almost every other kind worker including those in illegal trades come from the Philippines, Thailand, Indonesia, Cambodia or other nations in the area and can be found in almost every country of the world.

Many analysts believe the geopolitics of the area will again bring Southeast Asia to the center of the world’s stage. Most of the goods shipped around the globe still travel by sea, and Southeast Asia is the main hub for trade between Asia and the rest of the world. The volume of trade activity has been growing faster here than any other area of the world and most expect this trend to continue. The region’s great natural diversity may again come into play as the ageing populations of the developed world look for new medicines and natural cures from Southeast Asia’s biological resources.

According to one theory, the great Austronesian migrations of prehistory began with the flooding of the Sundaland continent, which also created the islands of the Malay Archipelago. The region’s natural treasures provided the wayfaring Austronesians with items of the trade that became valued in distant lands. Then, as now, a combination of natural forces thrust the people of Southeast Asia into a crucial role in the course of world history.

The Clove RouteAccording to Chau Ju-Kua, cloves and nutmeg were grown in two kingdoms found in Toupo, southeast of southern China.

Ships coming from Toupo to China sailed for twenty-five days on a northwest course before arriving at Sanfotsi, and from there proceeded either due to north to reach Tsu'an-chou (Fuzhou or Xiamen) or a bit northwest to reach Canton.

So it is clear and logical that the clove route went through the Philippines, where Sanfotsi was located and this also was the most direct course for the trade between the clove and nutmeg-bearing regions with the Chinese coast.

Share article:

Related links

More on the Clove Route

More on Clove and Cinnamon Routes

New evidence of Cinnamon Route from Mtwapa, Kenya

Serlingpa: King of Suvarnadvipa